Monarch season is long over in the north and we’re hearing reports of butterflies that have arrived in Mexico. It’s hard to believe that the three we released in September may be 2,000 miles away now! Here’s one last monarch post of 2015 to review our first season of raising.

I was an observer during the first generation of the season. During the second generation, we raised and released nine butterflies. During the migration generation, we raised four butterflies and released three (the fourth couldn’t fly).

I recorded 72 videos and took more than 900 photos, though I didn’t save nearly that many.

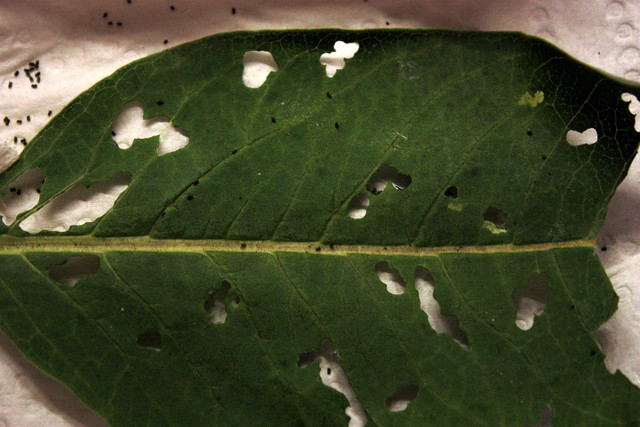

Why so few during the migration generation? I’m guessing it is because we had mostly common milkweed. By the time eggs were laid for the migration season, the common milkweed was not in great shape. I was imagining the female butterflies – who were still visiting the yard – saying, “Ew! I’m not laying my eggs on that disgusting leaf.” It’s a good reminder to diversify the plants to support a full season of insects. I’ve already planted swamp milkweed seeds and will look for more milkweed options next spring.

There was one pair of caterpillars that were always fighting for position. Even when they had climbed to the top of the cage, each was still trying to stake her claim. I felt like I was separating squabbling siblings more than once – “Just mind your own business. Move away so she doesn’t bother you.” – until I realized that I should leave them alone and let them figure it out.

Every day I brought in new milkweed leaves, ripping off bad spots. Many times late at night, I realized that I didn’t have enough and went back out into the yard with a flashlight to harvest more and save them in the fridge, just in case.

I never understood why they would always finish a wilted old leaf first, even when there was a new, fresh leaf available.

There were two “oops” caterpillars – two leaves I brought in for food had eggs I hadn’t noticed; one even got washed before I found it.

Right after molting, with no face…

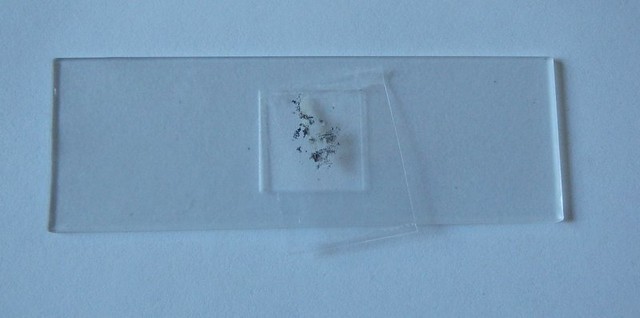

…because the head capsule pops off during molting:

The fascinatingly creepy skin that’s left over after pupation:

Once the skin didn’t detach when the chrysalis was formed, but it turned out fine.

A bigger concern: one caterpillar started discharging a yellow-green liquid the day before she pupated. I isolated her because I was worried about a disease that could spread to another caterpillar, or perhaps the caterpillar had been infected by a tachinid fly that would emerge from the chrysalis (and kill it) and make a mess. But the butterfly was normal.

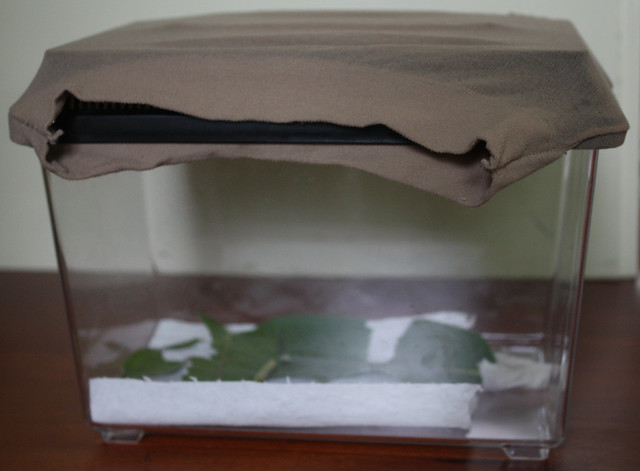

When a caterpillar is ready to pupate, it gets into position quickly; I only caught one caterpillar starting to make the long journey up to the top of the cage.

The caterpillars always seemed so surprised to find themselves at the top of the cage. “Wait, what is this green thing?”

They go through an elaborate process to spin a web during molting and before pupation.

And another long process to create the silk “button” that will hold the chrysalis.

I’m always surprised by how much I miss the caterpillars when they chrysalis-ize. Things are suddenly really quiet, once a chrysalis forms.

When the first butterfly was ready to emerge from her chrysalis, I was worried she would fall, so I set up lots of towels for cushion. But she didn’t fall, and neither did any other. In fact, one hung from the empty chrysalis all day, then all night, and into the next morning, when I opened the cage to let her out.

Right before the butterfly emerges, the chrysalis looks a little like Darth Vader.

It’s amusing how tiny and wrinkly the butterflies are when they first emerge. But it doesn’t take long for their wings to flatten.

They hold still for several hours while their wings dry.

One was so excited to leave that she tried to crawl through the towel that was draped over the top of the cage. I didn’t see her at first and was worried she had escaped.

But NONE of the butterflies escaped in the house!

All but one wanted help getting out of the cage. It’s a fun and funny feeling to have a butterfly crawl onto my hand.

All of them flew off into a tree immediately after they were released.

My favorite memory of the 2015 season: the sound of caterpillars chewing milkweed leaves.

Will we do it again next year? I’m not sure. It’s a lot of work – not so much on any one day, but over the couple of weeks during the caterpillar stage. It’s not possible to take a vacation while there are caterpillars. And some people advise against mass-rearing (although our “operation” could hardly be called “mass”), which makes me wonder whether we should raise any indoors.

It was a fun and educational experience, and I’m sure that I’ll want to do it again. It’s hard to see caterpillars in the yard and leave them, because I want to keep all of them safe until they turn into butterflies.